Professional Desk - INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS AND URBAN PLANNING: A Study of Guwahati City

Please feel free to contact me if you have any feedback on the article and required more information about the project and its firm. Meanwhile, we will be pleased to invite you to submit any good design project or professional article that you want to publish.

Suggeted citation:

YUVA and OEP.2019. Informal Settlements and Urban Planning:

A Study of Guwahati City. City Say. Guwahati, India.

YUVA and OEP.2019. Informal Settlements and Urban Planning:

A Study of Guwahati City. City Say. Guwahati, India.

Published by:

YUVA (Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action)

YUVA Centre, Sector 7, Plot 23, Kharghar, Navi Mumbai - 410210 (INDIA)

YUVA (Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action)

YUVA Centre, Sector 7, Plot 23, Kharghar, Navi Mumbai - 410210 (INDIA)

INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS AND URBAN PLANNING: A STUDY OF GUWAHATI CITY

Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) is a non-profit development organisation committed to enabling vulnerable groups to access their rights and address human rights violations. YUVA supports the formation of people’s collectives that engage in the discourse on development, thereby ensuring self-determined and sustained collective action in communities. This work is complemented with advocacy and policy recommendations on issues.

Authors:

YUVA - Brishti Banerjee, Syeda Mehzebin Rahman, Marina Joseph

OEP - Sneha Doijad, Ankur Choudhury

Field Support:

YUVA - Pooja Nirala, Minakhi Tamuli and Bhaskar Kalita

Maps:

Saurabh Chetia & OEP

Reviewer:

Doel Jaikishen

Layout and Design:

OEP

Maps:

Saurabh Chetia & OEP

W: www.yuvaindia.org

E: info@yuvaindia.org

Twitter: @officialyuva

Instagram: @officialyuva

Facebook: yuvaindia84

M: @yuvaonline

Youtube: officialyuva

Linkedin: officialyuva

Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) has conducted a series of planning studies across Indian

cities of which the study in Guwahati is the fourth in the series, following Ranchi, Bhubaneswar and Indore (YUVA & IIHS, 2017a) (YUVA & IIHS, 2017b) (YUVA & IIHS, 2019). The first two studies critically examined the discourse of ‘violations’ in planning, looking at both formal and informal developments and the third study examined ‘slums’ in the formal planning processes to draw implications for urban inclusion. These are envisioned to influence the urban planning discourse in India.

Each of the studies had two components—research and capacity building. The findings of research at every stage were taken back to the community to promote knowledge sharing. These capacity building sessions equipped people to engage with the technicalities of planning and use the same in their struggle for accessing land and adequate housing.

The study in Guwahati follows a similar framework. A preliminary review of literature and secondary data on Guwahati reveal the historical and multifaceted conflicts over land and it’s implication for housing. The city’s colonial past, migration, nationalist uprisings, land reforms and environmental conservation are some of the broad categories influencing the status of rights and claims on land. An economic and demographic review, on the other hand, shows decreasing growth rates and increasing unemployment (Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority, n.d.). Adding to this, Guwahati has been the site of high rates of development induced displacement since the 1950s. These incidents of

displacement are characteristically different from those in other cities, owing to the volatile relationship between communities and a growing concern over rapidly degrading natural areas.

Collectively, these conditions are shaping a unique informality, informed by deep rooted, intermeshed

politics. Formal planning processes have an equally historical journey, dating back to pre-colonial land

distribution and regulation exercises. Guwahati published its first post-colonial master plan in 1965. It is currently implementing its third master plan that will be valid till 2025.

Concurrently, the city is receiving central assistance for housing, services and infrastructure under schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), Swachh Bharat Mission and Smart Cities Mission to achieve the vision of Master Plan 2025, which is to make ‘Guwahati city one of the most admired state capitals of India and a gateway to the north-east, with a unique image of its own’ (Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority, n.d.).

In the last couple of years, Guwahati city and the state of Assam has been the focus of discussion and

confrontation for updating the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and its possible ramifications. The

question of the ‘stateless’ people that it may create has been raised. Thus, Guwahati stands at a crucial junction in its urban development trajectory in between development schemes and a contested citizenship landscape.

Within this context, this study was initiated by YUVA and Office of Emergent Practices, Tezpur (OEP), with the objective to map the city’s informality, particularly informal settlements in the narrative of formal planning processes and review this juxtaposition in the context of the earlier-described influences.

The study was conducted through both primary and secondary data collection methods. Through secondary data the status of planning in Guwahati and mapping of all slums has been undertaken. For primary data, this study used a mixed methodology combining both qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative tools included quasi-participant observations through transect walks in sampled settlements, and focus group discussions (FGDs) with residents. Quantitative tools included a semi-structured questionnaire for a sample survey for the purpose of this study, seven informal settlements were selected as a sample based on diverse locations, zones and geographical conditions in the city.

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and household surveys were conducted in these settlements.

In this report, we briefly capture the context of urbanisation and migration in Assam, further looking

at the status of informal settlements in Guwahati. The local planning bodies have a big vision to make

Guwahati stand out amongst other state capitals and transform Guwahati as a gateway to North East India. In this report we enquire whether these spatial planning strategies, city policies and visions recognise exclusion and inequality to support inclusive growth? Does it focus on the issues of growing informal settlements within the city and does it address the issues of inadequate habitats in informal settlements?

In the Comprehensive Master Plan (CMP) for Guwahati with perspective 2025 pockets of slum settlements are identified and the objectives stated envision Guwahati as a city without slums. We delve deeper into this topic and discuss the following in the report. Firstly, the importance of recognising informal settlements by understanding their historical background and how they have evolved over the period of time. Secondly, analysing the current context of Guwahati’s urbanisation and the status of informal settlements by mapping the slums against Guwahati’s Master Plan. Thirdly, understanding the typology of the slums by doing a household level study.

1. introduction

'Jhuggi–Jhompdi’ in Delhi, ‘Jhopadpatti or Chawls’ in Mumbai, ‘Ahatas’ in Kanpur, ‘Cheris’ in Chennai, ‘Keris’ in Bangalore and ‘Bustees’ in Kolkata and Assam the concept of slums and their definition might differ considerably across the states depending upon the socio-economic conditions and local perception. But nonetheless the physical traits are usually identified to be an unorganised cluster of hutments, inadequate basic amenities, insufficient arrangement for drainage and for disposal of solid wastes and garbage resulting in subliminal and unhygienic living conditions (Census of India, 2011). The Census (2011) enumeration of a ‘slum’ is questionable due to its exclusionary nature. Contrast this to the NSSO 65th round (2008–09) definition of the slum as a cluster of 20 or more households, which is nearly a third of the ‘60–70 household’ cut-off that Census 2011 uses. This significant shift has led to major under-counting of slums in India. Further, the Census of India 2011 classifies ‘slum settlements in India as the following: a) Notified slums are areas in a town or city declared as such under any statute including Slum Acts, b) Recognised slums may not be notified under statutes but are acknowledged and categorised as slums by State or local authorities, c) Identified slums are areas with at least 300 residents or about 60–70 households of poorly built congested tenements, in unhygienic environments usually with inadequate infrastructure and lacking in proper sanitary and drinking water facilities that are identified by the charge officer and inspected by a nominated officer by the Directorate of Census Operations and d) A non-notified slum is one which not notified as per the Census definition, and can be regarded as part of the ‘non-slum’ category.’ For the purpose of this report, we will be focusing particularly on non-notified slums, The term ‘informal settlement’ has been used to describe these settlements throughout the report.

In the past, the concentration of informal settlements was fairly limited to the mega cities and urban agglomerations. They not only dominate the capital cities of the world, but have also emerged in the second and third tier cities, whose growth curves are ascending and income opportunities are soaring (Davis, 1946). YUVA and IIHS’ extensive study on slums in Ranchi, Bhubaneswar and Indore focused on planning vis-àvis informal settlements, urban equity and inclusion in these cities. Through this report, we study the status of various types of slums within the Guwahati Master Plan. Guwahati being the largest city in North-East Region of India is an interesting mix of culture, people and topographies. It is the trade capital of the region and provides economic opportunities to the migrating population. It holds a high concentration of people who have migrated from rural Assam and also neighbouring states.

1.1 urbanisation of assam

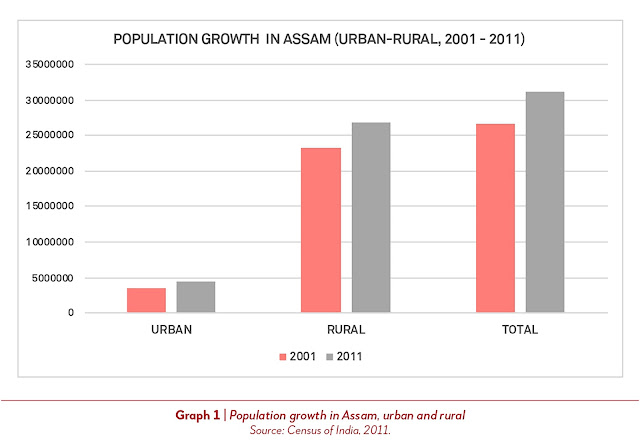

The state of Assam occupies a land area of 78,438 square kilometers (Census of India, 2011). A 22-kilometre strip of land, known as the Siliguri Corridor, connects the state to the rest of India. Assam has a heterogeneous population with socio-cultural and ethnic diversity. According to the Census of India, 2011 the population of Assam stands at 312.05 lakh of which 159.39 lakh are male and 152.66 lakh are female. The decadal growth of the state’s population was 17.07 per cent during the decade 2001–2011 as against 17.68 per cent for the country as a whole. It is the sixteenth largest state interms of area and fifteenth in terms of population size.

Out of the total 312.05 lakh population, 86 per cent live in rural areas and 14 per cent live in urban areas of the state. The density of the population of Assam has increased to 398 persons in 2011 from 340 persons in the 2001 Census, or on an average, 58 more people inhabit every square kilometre in the state as compared to a decade ago (Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Govt. of Assam, n.d.)

Assam has the largest urban population of 4.3 million (Census 2011) amongst the northeastern States. Guwahati, the biggest city of Assam, has an urban population of about 0.9 million, while the other large cities of the state are Nagaon (population 116,355), Dibrugarh (population 138,661) and Silchar (population 172,709). This indicates that other than the concentration of more than 25 per cent urban population of Assam in Guwahati and the surrounding urban agglomeration, Assam has a well distributed urban population across the state. The state’s level of urbanisation is 14 per cent in Census 2011, which is a 1.2 percentage point increase over the Census 2001 urbanisation level of 12.9 per cent. However, it is lower than the all-India annual rate of urbanisation, which was 2.82 per cent per annum from 2001–2011. The decadal growth rate of the state between 2001–11 was 15.47 per cent for rural areas and 27.89 per cent for urban areas. Additionally, considering the criteria of the definition of urban it is important to note that Assam may be more urban than it seems.

1.2 guwahati city

Guwahati city is situated between the banks of the Brahmaputra River and the foothills of the Shillong

plateau, flanked by Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport to the west and the town of Narengi to the east. It has gradually expanded as North Guwahati to the Northern bank of the Brahmaputra. The city is situated on an undulating plain with varying altitudes of 49.5 metre to 55.5 metre above mean sea level. Guwahati has a humid subtropical climate. The average annual temperature is 24.2 °C.

The city’s population grew from just 2,00,000 in 1971 to more than 5,00,000 in 1991. In the 2001 Census, the city’s population was 8,08,021. As per Census 2011, the total population of Guwahati is 12,60,419. The decadal growth rate of the population of Guwahati is 18.95 per cent as represented in Table 2.

The city experienced a massive population increase in 1971–81 and 1981–91. When the capital of Assam shifted from Shillong to Guwahati in 1972, a large number of people migrated into the city from rural Assam and other states of the north-east region of India. The formation of Bangladesh in 1972 also influenced cross-border migration. From 1979–85, the state of Assam witnessed the anti-government campaign ‘Assam Movement’, Assam Agitation, or Asom Andolan. It was against the enfranchisement of illegal immigrants. The 1981 Census could not be held due to the political unrest in the state.

Since then, the Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) area has registered a slowing down of population growth rate, from 3.3 per cent per annum in 1991–2001 and 1.8 per cent per annum in 2001–11. In the last decade, the GMC area has experienced a growth rate that is even lower than that of Assam’s urban population growth rate of 2.5 per cent per annum. The Guwahati Metropolitan Area (GMA) has registered a population growth that is even lower than that of the GMC rate from 2001–11. This means that the migration rate to the city has slowed down in the decade of 2001–11 due to either decline in migrants from other north-eastern states and rural Assam or the decline from cross-border migration or both. Therefore, contrary to the expectation, the population of Guwahati city and its metropolitan region has stabilised since 2001 due to economic and geopolitical reasons. Nevertheless, all these have created pressure on the existing infrastructure and urban amenities (Desai et al., 2013).

Based on the past population growth trends—low, medium and high—population estimates for Guwahati Metropolitan Area for the period 2005 to 2025 is estimated to vary from a low of 19.10 lakhs to a high of 22.50 lakhs in 2025. According to the Master Plan Report prepared by Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) the total population of GMA will be 21 lakhs approximately in 2025, as represented in Table 3.

1.3 governance

In 1878, the Government of Assam adopted the Bengal Municipal Act 1876, which provided for urban local bodies of four classes. Accordingly, Guwahati was constituted into a firstclass municipality. Guwahati continued to be a municipality till 1969 when it was upgraded to a Municipal Corporation with the enactment of Guwahati Municipal Corporation Act (Guwahati Municipal Corporation, 1969).

Guwahati Municipality was converted into a corporation in 1974 with 34 wards and 62 villages (Borah, 1985). It is the local body responsible for governing, developing and managing the city. Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) is further divided into 31 municipal wards and 90 Area Sabhas in a 3-tier hierarchy. GMC administers an area of 216 square kilometres, (Refer Map 2).

The Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) was established in 1992 as per the Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority Act 1985. It replaced the erstwhile Guwahati Development Authority constituted in 1962 under the Town and Country Planning Act, 1959 (amended) (Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority, n.d.-b). It is a developing authority responsible for planning and development of the Greater Guwahati Metropolitan Area (GMA), (Refer Map 3), and for revising the Guwahati Master Plan and Building Bylaws to cover an area of 3,214 square kilometres by 2025.

The region delineated under GMA constitutes areas of Guwahati Municipal Corporation, North Guwahati Town Committee, Amingaon Census Town and 21 revenue villages (Abhoypur, Rudreswar, Namati Jalah, Gouripur, Silamohekhaiti, Tilingaon, Shila, Ghorajan, Mikirpara, Kahikuchi, Mirjapur, Jugipara, Borjhar, Garal Gaon, Ajara Gaon, Dharapur, Jansimalu and Jansimalu).

The Guwahati Development Department (GDD) is a special department of the Government of Assam, formed for Guwahati’s overall development. Guwahati is one among 100 Indian cities selected for the Smart Cities Mission, under the project launched by the Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India.

1.4 urban morphology

Guwahati has a mix of plain areas, low-lying marshy lands and hills, with the Brahmaputra River running across the length of the city in the north (Mahadevia et al., 2014). Guwahati’s ‘urban form’ radiates from a central core, with growth corridors radiating and extending towards the south, east and west. The core area consists of the old city with Pan Bazaar.

Paltan Bazaar, Fancy Bazaar and Uzanbazar which were the main urban centres of the city. But in the past few decades, southern Guwahati areas such as Ganeshguri, Beltola, Hatigaon, Six Mile and Panjabari began forming a southern sub-centre surrounding the capital complex at Dispur.

While Paltan Bazaar is the hub for hotels and the nodal point for transport services, Pan Bazaar is centred on educational, administrative and cultural activities in addition to offices and restaurants. Fancy Bazaar is the commercial hub for the retail and wholesale market in northeast India and Uzanbazar mainly contains administrative, retail, dining and residential areas. With these bustling areas, the city core is a busy and lively part of Guwahati. Ulubari, Lachit Nagar, Silpukhuri, Chandmari and Zoo Road (R.G. Baruah Road), which have a mix of retail–commercial and residential areas, can be considered as extended parts of the core.

Among the city corridors, the most important is the corridor formed along the Guwahati–Shillong (GS) Road towards the south (almost 15 km from the city-centre). The GS Road corridor is an important commercial area with retail, wholesale and commercial offices developed along the main road. It is also a densely built residential area in the inner parts. The capital Dispur is situated in this corridor. This corridor has facilitated the growth of a southern city sub-center at Ganeshguri, along with other residential areas to the south developed during the past few decades.

1.5 history

The history of Guwahati city dates back thousands of years. It has witnessed many ancient kingdoms on its lands. In mythology it is known to be the legendary city—Pragjyotishpur (may mean ‘the city of Eastern Astrology) (Gait, 1963). The ancient Shakti temple of Goddess Kamakhya located within the Nilachal hill of Guwahati, the unique astrological temple of Navagraha in Chitrachal Hill, archaeological remains in Basistha and other archaeological sites are testimonials to the historical and mythological importance of the place.

According to the Assam Buranji (Dutta, n.d.) or A History of Assam, the town of Guwahati continued to be the contested land for power between the Ahom Kingdom and the Mughal Emperor till the 16th century. In 1825, Assam was surrendered to the East India Company under the British Raj. The British Annexation of Assam in 1826 was critical in the history of growth and development of Guwahati. The town was connected by railway line with the rest of India in 1890. After the partition of India, Guwahati experienced phenomenal growth and was made the headquarters of the province of the north-east for several years. In 1972, after the reorganisation of the Assam state, the capital was shifted from Shillong to Dispur (Guwahati) whereby the city gained enough political importance. Since then, the city has grown enormously in terms of population and development of commercial activities (Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority, n.d.-a)

1.6 land and migration

Historically, the Ahom Kings owned all land in Assam. They later made extensive revenue free land grants to temples, priests, and charitable institutions (Sharma, 2013a) But the bulk of land was allotted ‘to paiksor corvée labour’ (as a parcel of 2.66 acres), in lieu of their services to the state (Das, 1986), which then came to be recognised as private property under the control of the clan that received the grant. The British period saw the transfer of ownership of all lands into the hands of the state and allowed only occupancy rights through the lease to their occupants, which were deemed permanent, heritable and transferable, subject to regular tax payment. The lease rights were initially for a period of one year only, which was extended to 10 years (called periodic lease) if the occupants proved that they had permanent homesteads on or were cultivating the land. Both types of leases, whether annual or periodic, were however renewed at the end of the lease period (Ibid.). The Contemporary Assam Land Policy from 1989 for granting land rights (pattas)is based on this historical land transfer policy as we see later. Religious institutions were exempted from paying taxes on the land they had (Saikia, 2012; Sharma, 2013a). The poor peasants who received lands under ‘corvée labour’ but could not pay the taxes sold their lands and settled on wastelands in remote areas, creating a base for future conflicts with

the state. The British government’s Bengal Forest Act marked ‘reserve forests’ for the use of the state, i.e., the British state. This implied that the British could decide on the use of the forestlands, which it began to give away to individual landholders for tea plantations, to the railways and most importantly to the marginal and landless peasants for agriculture. The latter got the land, however, in exchange for their labour in collecting forest resources and other such activities on behalf of the colonial forest department. Such settled villages were known as ‘forest villages’, which refer not to villages located in the forest, but to villages or colonies of ‘coolies’ or labourers established by the forest department for assured supply of labour required for forest work. The tribals, the original occupants of forests, were allowed to settle and use forestland for a temporary period and hence were considered encroachers while the dwellers of the ‘forest villages’ were given permanent rights, leading to conflicts between the two groups.

India continued with the same forest legislation, with the continuation of conflicts about forestland rights in Assam as well as the rest of India. In Guwahati, the original tribal communities of the region

and those who have migrated in the last 50 years too are occupying forestlands while the other populations have purchased lands from those who were granted pattas during the British period. Between 1830 and 1870, a significant amount of land was transferred to planters for plantations (Sharma, 2013a). Since the indigenous population refused to work on these plantations, tribalmigrant

labour was brought from Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Bengal (Srikanth, 2000). For further commercial exploitation of land resources, the British government, with the support of the Assamese zamindars, encouraged the Bengali Muslim peasants from East Bengal to migrate to the Brahmaputra Valley for jute cultivation. During the colonial period, to protect the identity of tribal communities, tribal belts were formed in Guwahati as well as in the rest of Assam. For example, the current Greater Guwahati area was under the South Kamrup Tribal Belt prior to shifting of the state capital to Dispur (Sharma, 2013a). Post-independence, the tribal lands of South Kamrup were acquired through dereservation, leading to evictions of the resident tribals without giving them any alternative. The land mafia too forced some of the tribals to sell their lands (Sharma, 2013a). Both these factors forced these tribals to occupy forestlands in the hills, at the cost of being called encroachers later on. There were also tea estates on the hills that were leased to the planters by the British and had to be returned back to the state if tea plantations ceased to exist. On expiry of the 99-year lease of the Sunsali tea estate, the state government gave part of it to the Guwahati (Noonmati) Refinery and its colony (Mahadevia et al., 2017).

In the case of Guwahati, the ‘encroachments’ on wetlands and hills have set the stage for conflict about housing rights, especially for those without legal land tenure. This has led to a cycle of violence and counter-violence. The informal settlers’ conflict with the state for land rights on the one hand and resistance against evictions carried out in the name of ecological protection on the other have turned into a political movement and laid the foundations for permanent conflicts in the city. The land rights conflict and its inherent violent nature is embedded in the state’s particular land policy history, ethnic conflicts and long drawn violent political movement against the immigrants, particularly from across the border from Bangladesh, labelled as ‘Muslim infiltrators’, and conflict of indigenous people (tribals) on the land issue. Guwahati’s geography has led to restricted land supply and the high value of land has led to continuous process of encroachments (dakhal) for accessing land for housing, and the selectivity in the state government’s approach to ecological conservation in Guwahati, leading to evictions of the settlements of the poor and denial of their land rights (Mahadevia et al., 2017).

Guwahati city is characterised by numerous hills and highlands scattered all over, along with swamps, beels (water bodies/wetlands) and low-lying areas and reserved forests on the hills. The city is bound by the river Brahmaputra and Khasi–Garo hill ranges to the north and south, respectively. There are five hill ranges, marked as reserved forests, under the Kamrup East district (within which Guwahati is located); the Guwahati, Garbhanga, Sonapur, Rani and Palasbari ranges. The city also has many wetlands, namely, Silsako, Bondajan, Surasola, Borsola and Deepor, among which the last one is protected under the Ramsar convention (Mahadevia et al., 2017). All these beels have been notified under the Assam Hill Land and Ecological Sites (Protection and Management) Act, 2006. These natural features have led to an uneven spread of population in the city, on the one hand, and a sprawl along the east-west axis. The sprawl not only adds to increased travel time and costs and hence greenhouse gas emissions, but also results in high land prices.

The Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) area registered a population growth rate of 8.1 per cent per annum during the 1971–91 period (Mahadevia et al., 2014), following the setting up of the capital at Dispur in 1972. The migrants consisted of those employed in the state administration, students and labour from states such as Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Bihar who work in sanitation services. The affluent population from the rest of Assam also bought houses in Guwahati as a measure against long insurgency problems. It goes without saying that the government and public housing was insufficient. All these dynamics have led to largescale informal developments through a process called dakhal(encroachment), however, mainly on ecologically sensitive areas such as hills and wetlands and the lands reserved under the city master plan or Urban Land (Ceiling and Regulation) Act (ULCRA) of 1976, as that was available to the state, private developers and lowincome households. The dakhal was either by the people themselves, as in the case of the tribals who encroached on the hill lands or by middlemen (Mahadevia et al., 2014; Desai and Mahadevia, 2014) or by the state itself on behalf of various institutions and the private sector. This has led to a differentiated approach by the state government in legalising the dakhals, leading to resentment among the low-income population and led

to the land rights movement as we discuss later. An estimated 65,900 households were residing on 16 hills in2009, wherein 71 per cent of all households were living on government land, 18 per cent on reserved forestlands, 7.3 per cent households on patta land owned by others, and 3.6 per cent on patta land under their ownership (Nielson, 2011).

The Assam Land Policy, 1989 (Government of Assam 1989) gives priority of land allotment (pattas) to the indigenous people living in Guwahati or other towns on payment of the prescribed premium. The order of preference is for firstly giving pattas to the indigenous people occupying government land for 15 years and not having any land in the rural or urban areas of the state and after that to others with Assam domicile and who have been living in the city for 15 years without owning any land in rural or urban areas. No priority is given to the households established on railway land. The issue of domicile of Assam has been a point of contention through the last 50 years of the state’s history (Mahadevia et al.,

2017).

There was also a flow of people from other states to earn their livelihood via different economic activities. There has been migration from Bihar, Andhra Pradesh and Punjab since the colonial period (Desai et al., 2013) for employment; due to floods, river erosion and droughts in their native place destroying sufficient cultivable land; to escape rural poverty, etc. All these trends in migration help categorise those living in informal settlements as:

1. Those who left their native place on their own accord for employment.

2. Those who were forced to leave their native village due to the natural disasters, poverty and other

reasons.

3. Those who have been living in the slum areas through generations. (Ibid.)

1.7 growth of informal settlements

Early Settlements

The early informal settlements in Guwahati started in colonial Assam. As the town became the administrative headquarters, initially of the province in the east and later of the district, it grew in size and with growth arose a need to build and maintain a sanitation system to safely dispose of sewage and garbage. This need was further compounded when Guwahati was connected to the Eastern Railway network and with the rise in the shipping industry, which resulted in the enhanced movement of temporary populations in the town. To cater to the demands of sanitation maintenance, the colonial authorities brought people (safai karmacharis) belonging to Dalit communities from other states of

India as workers. The very nature of their work created a certain stigma and compelled them to live in isolation in small colonies with very poor facilities. These were the first informal settlements of the city, often called ‘Harijan colonies’, housing the municipal workers and their families.

With the increase in population in these colonies by internal growth and in-migration, the conditions within these confined areas deteriorated. The first Harijan colony as per records was said to be located on M.C. Road. Over time, several such areas sprouted across the city, sheltering people migrating to the city for employment and livelihood opportunities. They are majorly engaged in institutions and organisations like the railways, university, hospitals, government offices, etc. (SsTEP and Action India, 2004–05).

Housing for Low-income Residents

When the capital of Assam shifted from Shillong to Guwahati in 1972, a large number of people migrated into the city. Formal sector housing, which also included the formal sector rental housing, was unaffordable to the poor. The 1824 rental-housing units built by the Assam State Housing Board at various locations in the city was not adequate to fulfil the housing needs of the poor. Based on the research conducted by Centre for Urban Equity–CEPT University, one of the sites revealed that

many of the Assam State Housing Board’s economically weaker section (EWS), and low-income group (LIG) rental units are taken up by higher income occupants and their families. Due to this disparity and other exclusionary reasons, the low-income residents have turned to the informal land and housing sector, which also included the informal rental sector (Desai et al., 2013).

The location of these informal settlements and its growth and distribution is based on economic activities and the availability of land. The research also categorised the informal housing sector into several housing submarkets created through the land and development processes (Desai & Mahadevia, 2013).

The categories are:

• Through informal occupation, commonly known as ‘dakhal’, in public and private lands.

Such dakhal is majorly located on:

– Railway lands

– State government’s revenue lands ( located in the plains, on swampy lands and in the hills)

– State government’s reserve forest lands mostly in the hills

– Private lands earmarked for acquisition

– Other private lands

• Through land alienation, majorly located on:

– Private agricultural lands on the city’s periphery.

It is an important observation here that in Guwahati the poor as well as the middle class have engaged with ‘dakhal’ to get access to land. Contrasting characteristics of dakhal can be witnessed here. While the informal settlements of the middle class can make good quality housing and get access to basic services, the majority of the informal settlements consist of poor quality housing and lack of basic services. The Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) has identified some informal settlements as ‘slums’ over the years to provide access to government schemes. In Chapter 4, we discuss the details of these informal settlements and their identification over time.

2. planning in guwahati

2.1 master plans in guwahati

The First Master Plan and Zoning Regulation adopted in 1965, modified in 1986, covered regulation, control and guidance patterns till 2001. The zoning regulation was not followed and over the years the core area of the city was developed densely with intermixing of residential, commercial, public and semi-public activities. The task of the plan implementation was assigned to several agencies, including the development authority, the Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) and some of the government departments (Journals of North East India Studies, n.d.). However, there was no land management

policy detailed for the non-conformity to the statutory practice of regulation and control. The Master Plan did not fully consider the broader urban development strategy. It did not stretch beyond the limits of the metropolitan region and as such the question of linking with a regional plan was not dealt with. As a physical development plan, it ignored the potentialities of hillocks in and around the city as viable centres of tourist and recreational spots. In the absence of financially viable investment packages through site development, etc., proposed programmes and projects were implemented in a piecemeal manner.

Guwahati’s First Master Plan,1965 (Perspective 1986)

To deal with rapid urbanisation and related urban issues, the State Government prepared a Master Plan

for Greater Guwahati in 1965 under Section 10 of the Assam Town and Country Planning Act, 1959. The Plan had Perspective 1986.

Guwahati’s Second Master Plan, 1987 (Perspective 2001)

The Modified Final Master Plan and Zoning Regulations for Guwahati was prepared by the Town and Country Planning Organisation by exercising the powers under section 14 and sub-section (2) of section 10 of the Assam Town and Country Planning Act. It was published in February 1987. The 1987 Master Plan was entrusted to the Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (which was constituted under Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority Act 1985) for implementation of

the Plan with Perspective 2001.The total area covered under the Guwahati Metropolitan Area (GMA) is

approximately 262 sq. km.

Guwahati’s Third Master Plan, 2001 (Perspective 2025)

The Master Plan and Zone Regulation up to 2025 was adopted in 2009, after a gap of a few years, incorporating more villages with an addition of 66 sq. km. The Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) in its bid to fulfill one of its statutory obligations to prepare, enforce and execute the Master Plan took initiative since 1995. The existing Master Plan did not include the project for the capital of the state. The capital was established with temporary planning. Increase in traffic load at an alarming rate and the ever expanding traffic nodes added a new dimension to the land use pattern. There was another urgent need of revitalisation of the land development process in the light of increasing settlements on the vacant land, including the Green Belt, which constituted for 37.16 per cent of total planning area. The GMDA Act provided for acquisition of land by the Authority and it was recognised that urban land can be used as a major resource to raise funds by acquiring, developing and providing service plots to the consumers. The office records and public declarations showed such awareness. But till 2009 the Master Plan approach was sidelined. The sprawling growth of the city could not be regulated. ‘Development’ as defined by the prevailing acts refer to building activities on land. In the city, from this point of view, 75 per cent development activities occur due to housing activities. The construction of parks, roads or beautification constitutes only 25 per cent of total development activity. So, it can be logically perceived that if the development activities of this larger section undertaken mostly by private sector housing activities can be guided in the right perspective, much of the development targets are fulfilled. The non implementation of the existing Master Plan and the non-existence of a plan for a long period are major constraints in the management paradigm.

The approach of the present Master Plan (2009–2025) touches the question of dispersed urbanisation and reduction of congestion and improvement of inter and intra-regional accessibility. There has also been a change of authority for planning, from the Town and Country Planning Organization to the Development Authority. Besides the shift of authority, the notion of urban planning assumes a crucial turn in the context of the 12th Schedule of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act. The Act envisaged community participation in the planning process. However, no initiative was taken by the state government in this context. The role of the corporation as a civic body was restrained by the fact that it is dissolved by the Government from time to time. In the last few decades, the elected body could operate only for a few years and this greatly hampered the objectives of city government in a growing city (Sharma, 2013a).

Comprehensive Master Plan, 2025

The 2001 Master Plan was subsequently revised with Perspective 2025 under the GMDA Act, 1985 (Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority, n.d.-b). The plan is called the Comprehensive Master Plan 2025 (CMP– 2025) wherein the proposed Greater Guwahati Area has a total area of 328 sq.km., an increase of 66 sq.km. from the previous plan including 13 planning units and 3 units of three new towns. According to the CMP 2025, the Master Plan envisages to transform Guwahati to one of the most admired state capitals of Indian and create a unique image of its own as the gateway of north-east

India.

Vision and Goals, 2025

To achieve this vision, the necessary goals and objectives are formed as follows:

Goal 1: To conserve Guwahati’s sensitive natural environment.

Goal 2: To develop an integrated intra-urban transport system.

Goal 3: To develop well-distributed physical and social infrastructure

Goal 4: To provide space for efficient functioning of economic activities

Goal 5: To create an image befitting that of the state capital

Goal 6: To create affordable housing for all and develop a city without slums

Goal 7: To bring in a system in the land development process

Slums and the Comprehensive Master Plan

Based on the report on the Master Plan for Guwahati Metropolitan Area, Map 4 highlights the locations of slums/informal settlement pockets in the city. According to the information provided by the Town and Country Planning Department, 26 pockets of slum are identified in the GMC area. These pockets house around 0.16 million persons (about 20 per cent of the total population). The following measures will be taken to upgrade/rehabilitate the existing pockets of slums to achieve the vision of a city without slums:

1. In case of existing slums, which are on government lands that are not needed for development of

any infrastructure or other urban activities, plans for upgrading of slums may be prepared and

implemented.

2. Other slum pockets may be resettled at appropriate areas with due consideration of their distance from workplaces.

3. In all new housing schemes, at least 30 per cent of total housing shall be one-roomed houses, part of

which will go to the urban poor generally living in slums. These may be provided with cross-subsidy.

2.2 planning units

The Guwahati Master Plan–2001 had divided the Master Plan area into nine spatial units called planning units. In CMP–2025, Planning Unit 1 of the 2001 Plan has been subdivided to distinguish between the Central Business District and extended areas. Thus, the existing GMA–2025 has 13 planning units (including 3 units of the three new towns).

The GMA–2025 area is further sub-divided into small spatial units called Planning Subunits (PSU). A total of 74 PSUs has been identified, including three new towns proposed for 2025. The PSUs 1 to 60 are co-terminus with municipal wards within the GMC area; beyond the GMC area, PSUs 61 to 71 are delineated by grouping villages. PSUs 72, 73, 74 are respectively the new towns I, II and III.

2.2 other plans in guwahati

Guwahati, as the only metropolitan city in the state, has witnessed the introduction of several national flagships programmes like the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) with state rules and regulations, which applies to the informal settlements also. Apart from this, the state has also been undergoing a process of identifying ‘citizens’ through the National Register of Citizens (NRC). A brief note on all these processes of implementation is explained to provide context on schemes that are implemented in silos, without clear linkages with the Comprehensive Master Plan

(CMP).

Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana Mission (Urban)

PMAY–U is a national flagship programme of the Government of India and is presently being minutely

monitored at the district level by the State as well as Central Government. The cell was formed in Guwahati, Assam, in July 2017, while the scheme was launched in 2015. Using the Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) survey data that states that 163 informal settlements exist in the city, and most of the informal settlements are established on railway land, a survey was to be carried out in all the slums through an intermediary organisation that would conduct participatory research in all the slums. PMAY housing application forms were to be filled accordingly.

However, over a period of time the agenda was changed and Form-A (which is for in-situ slum rehabilitation [ISSR]) was distributed to the community leaders of each slum. They identified a list from the previous Rajiv Awas Yojana scheme, which included 163 slums in Guwahati and their land ownership showed that most of the slums were on railway land, state government land, wetlands and private lands. It was observed that the Beneficiary Led Construction (BLC) component was promoted by PMAY–U as it includes the households who had land leases (miadi patta) and could be easily connected to banks for release of loans and building purposes.

A Right to Information (RTI) application response (PMAY, Assam City Mission, n.d.), revealed that only 24 slums have been surveyed by the PMAY–U Assam department in the ISSR category, but no datasheet was prepared and no recorded details were found. The PMAY Assam Mission Director, stated that the reason behind the nonimplementation of the ISSR component was that none of the slums in Guwahati were notified or regularised by the state, resulting in the non-utilisation of the allocated budget and nor was the Detailed Project Report (DPR) prepared for the same. The primary challenge for rehabilitation and resettlement of slums, according to GMC officials is reservation of revenue land in urban areas by the department for which there is no progress of the scheme or utilisation of funds (Mission Director, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, n.d.).

The central issue for implementation of the ISSR component of PMAY is land. The informal settlements in Guwahati are mostly established on railway land, which needs to be denotified from the central agency owning it. Internal conflicts between the State and Central Government Departments acts as a challenge in implementation. Also, the Additional Commissioner of GMC has mentioned that GMC has no land of their own for any development or to implement any schemes and if the Revenue Department provides them land, it will be kilometres away from the city where the people will not

shift (Additional Commissioner, GMC, 2019). Therefore, land is the major question in the city at present.

According to The Assam Slum Areas Improvement and Clearance Act, 1956, Town & Country Planning is the official authority to notify, survey and regularise slums in towns and cities, other than Guwahati. Another reason for non-implementation of the ISSR component is the non-notification and recognition of informal settlements in Guwahati due to the absence of an official agency responsible for it. The main progress on PMAY (urban) has been made under the BLC component, where 80,554 beneficiaries have been identified for release of the Central and State Subsidy of INR 2 lakh to each

beneficiary. Till date, 33,000+ houses are grounded, 2,600+ are completed and 10,000+ are nearing

completion (Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana–U, n.d.).

Swachh Bharat Mission–Urban

A significant population of Assam still does not have access to sanitary latrine systems, causing major

environmental and health risks. Majority of the houses in the informal settlements use pit latrines, and due to the absence of drainage systems and linkages to pipelines, it creates an unhygienic and unhealthy environment. Although the Swachh Bharat Mission–Urban Assam, in cooperation with all urban local bodies (ULBs), has identified the prevalence of unsanitary/kutcha latrines under the administration of ULBs across Assam, sufficient progress has not been made by the department. From a survey report received from the ULBs, the Mission has sanctioned 68,338 units of household latrines and 2,280 community/public toilets. It is however relevant to state that ‘No Latrine’ cases rarely exist in Assam due to the presence of pit latrines. On the basis of all these facts and figures, the State Mission Directorate envisaged declaring Assam, 100 percent open defecation free by 2 October 2017 (Swachh Bharat Mission–Urban, n.d.).

Advocacy with SBM on the process of implementation of the schemes through an RTI application (PMAY, Assam City Mission, 2018), reflected the status of its implementation in Guwahati and revealed that no community toilets had been constructed by the department despite being an important vertical. Seven public toilets were constructed but their adequacy remains questionable and crores of rupees were spent on building these toilets. For individual household latrines, the beneficiaries were capped at 6,777 citing budget restrictions. The RTI was able to provide a clear representation of the inadequate implementation of the scheme so far (PMAY, Assam City Mission, 2018)

National Register of Citizens (NRC)

The NRC in Assam is a list of Indian citizens living in the state. The citizens’ register sets out to identify foreign nationals in the state that borders Bangladesh. The process to update the register began following a Supreme Court order in 2013, with the state’s nearly 33 million people having to prove that they were Indian nationals prior to 24 March 1971. The updated final NRC was released on 31 August 2019, with over 1.9 million applicants failing to make it to the list. In Assam, one of the basic criteria was that the names of the applicant’s family members should either be in the first NRC prepared in 1951 or in the electoral rolls up to 24 March 1971. Other than that, applicants also had the option to present documents such as refugee registration certificate, birth certificate, LIC policy, land and tenancy records, citizenship certificate, passport, government issued license or certificate, bank/post office accounts, permanent residential certificate, government employment certificate, educational certificate and court records (Business Standard, n.d.).The urban poor and migrant workers in Guwahati faced a number of hurdles in proving their citizenship through legal documents. Reasons such as change of residence, lack of awareness and dependence on others for filing of applications due to illiteracy resulted in individuals’ names not being included in the draft list. First, this section of the population faces difficulty in finding rented houses with their minimum earnings, forcing them to settle in the existing slums, hills, wetlands and other state bare lands. Second, because of their settling in these lands they are susceptible to forced evictions from the administration from time to time. Frequent evictions or threat of evictions results in compelling them to change their houses at regular intervals of time. Hence, it is common for people not to possess proper legal documents, or to have misplaced them during forced evictions or shifting or for other reasons such as destruction of personal belongings due to floods, erosion and regional conflicts.

Some of the major urban schemes mentioned have no mention in the Comprehensive Master Plan 2025. There is no effort to integrate the Master Plan with major urban schemes as they continue to exist in silos and do not integrate or communicate with the Master Plan and this can be identified as a major gap in the planning practice.

But if we look at the implementations of these centrally sponsored schemes, we will find that due to lack of proper planning and no mention of these particular schemes in the Comprehensive Master Plan, the benefits do not reach to the actual beneficiaries. Though the implementing agencies are different, there should be a connection in between the GR of the schemes and the city planning document. Therefore, this kind of conflict between the departments hinders the way in access to benefits by the people living in informal settlements.

3. research objectives and methodoloy

3.1 aim

The study aims to present the relationship of formal planning processes with settlements categorised as slums in Guwahati, to both evaluate the oversights and illustrate opportunities for new modes of articulation.

3.2 objectives

1. To map and generate a database of settlements categorised as ‘slums’ in Guwahati, overlaying their

status with applicable plannig norms.

2. To understand the nature of planning for settlements vis-à-vis formal planning processes.

3. To highlight the implications and influences of urban development processes on informal settlements and make recommendations for inclusive habitats.

3.3 methodology

Through secondary data the status of planning in Guwahati and mapping of all slums has been undertaken. For primary data, this study used a mixed methodology combining both qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative tools included quasi-participant observations through transect walks in sampled settlements, and focus group discussions (FGDs) with residents. Quantitative tools included a semi-structured questionnaire for a sample survey. There were two distinct stages of this research.

3.4 stages of data collection

Stage 1: Secondary Data Collection and Analysis

Secondary Data was collected to understand the planning process in Guwahati and create an exhaustive list of slums in the city. This data was collected from reports, surveys, publications, etc. by government authorities, private organisations and NGOs. The collated data was analysed in terms of age of the settlement, location, notification, tenurial rights and services. The following were the main outcomes:

1. Matrix: This was prepared from the collated data to do an in-depth study on the settlement listing, settlement timelines, ward numbers, identification in Master Plan, inclusion in Rajiv Awas Yojana surveys, etc.

2. Spatial Analysis (GIS): Based on the secondary survey, matrix and Guwahati Municipal Corporation

(GMC) identified slum pockets data, the settlements were geo-referenced on the land use Master Plan 2025. This spatial database was used to analyse the deviation in the land use Master Plan 2025 as the informal settlements were not recognised in the same.

3. Overlay Analysis (Google Maps): Based on the secondary database, matrix and GMC identified slum pockets data, settlements were geo-referenced on Google satellite imagery. This overlay along with the timeline was used to analyse the morphological evolution of the settlement from 2003–2019.

This overlay along with the timeline was used to analyse the morphological evolution of the settlement from 2003–2019.

Stage 2: Primary Data Collection and Analysis

For the purpose of this study, seven informal settlements (non-notified) were identified and selected for a casebased study. A purposive sampling strategy was used to identify the sampled settlements based on geographical feasibility and YUVA’s outreach and intervention. The seven settlements are located in diverse contexts, locations, land occupancy, scale, timeline and planning zones in the city.

1. Transect Walk: This included visits, transect walks across the sampled communities with local residents to explore the location, infrastructure and distribution of resources. The major observations were noted down in the form of field memos and were referred at the time of analysis. Additionally, during these walks a mobile application was used to map the geographical area of the settlements.

2. Focus Group Discussions (FGDs): In conjunction with the overlay study, FGDs were conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire in each of the sampled seven settlements. The discussion was conducted with the community members to understand the history, growth, occupation, livelihood and amenities available in and around the settlement. Further, to ensure a holistic representation, participants from varying age groups and gender were included. The findings of the discussion gave insight into the evolution of the informal settlements in Guwahati and how they have grown in terms of household and populations.

3. Household Survey: A household survey of two– three houses from each of the seven settlements (14 in total) was conducted. The documentation was done to understand the average size of a household in an informal settlement, the materials used for construction, space requirements and basic facilities. For this purpose, a questionnaire was developed that focused on acquiring information with reference to history of the settlement, land relationship, period of settlement relocation from any other areas within and outside the city, reason for settling on the present land, ownership of land (patta), land tenure, threats of eviction if any, services and amenities available in and around the settlements. During the

survey, a basic layout plan of the household was prepared based on measurements and recordings. In each diagram the access street of the basti was shown along with the location of the surveyed house, its adjoining houses, yard, community gathering space, and common shared spaces in proximity. This broader layout helps in establishing the context of the house in relation to its surrounding density

within the settlement.

4. Housing Typology Study: To understand the form of existing houses within settlements, architectural plans were prepared. Annexure 2 (2.1 to 2.6) shows the sketch of a household of 6 different informal settlements . A sketch of a household from Bhutnath Bagan is shown in Annexe 2.1. The plans highlight observations of the house, the pathway of the basti, entry to the house, sizes of rooms, adjoining houses, outdoor toilet/bath area and common gathering space outside the house. Additionally, to give a comprehensive idea of the condition and materiality of informal housing in Guwahati, a threedimensional figure of a sample/typical house in basti was drawn (Refer Annexure 3). The drawing highlights the layout of the house, structural composition, materials used for construction, finishing, roofing and temporary coverings.

5. Limitations: The time constraints for the project and limited resources did not allow for a physical cadastral mapping of all the identified settlements, hence the exercise was conducted digitally. Due to the rasterisation1 of existing and proposed land use, maps were manually georeferenced and digitised, therefore some deviations may exist in the overlay analysis between the maps and the actual conditions on ground. No new surveys to identify informal settlements were conducted. Due to limited resource persons the sample survey was conducted in only seven settlements.

4. key findings and analysis

4.1 listing of slum surveys and mapping

Over the last 25 years, a number of informal settlements’ identification surveys have taken place. Both government and non-government organisations and individual researchers have conducted these surveys. The purpose of each survey has been specific to the time it was done. Nonetheless, for the intent of this study we briefly look into the data collected in each of the surveys. The primary data that is beneficial for our study is the timeline of the surveys conducted, organisations involved, number

of slum pockets recorded, total population and number of households. With this data we have created a collated data matrix based on timeline surveys which highlight the status of identification of slums in Guwahati city.

Recorded Slum Surveys and Identification

Below is the brief summary of 8 slum identification surveys conducted by various government and nongovernment organisations between 1986–2017:

• The Director, Town and Country Planning, Assam, conducted a survey for detection of slum pockets in 1997. They identified 20 slums pockets in Guwahati City with a total population of 65,450 in 10,213 households.

• The Directorate, Municipal Administration, Assam, conducted another survey in 1997 to identify the slum and urban poor population in the Greater Guwahati Region. They listed a total population of

1,13,064 in 19,558 households, distributed over 40 slum pockets.

• The Guwahati Municipal Corporation conducted a survey in 2001, identifying 26 slum pockets with a total population of 1.6 lakhs (which was about 18 per cent of the total population of Guwahati City in 2001). Refer Map 5.

• For the purpose of implementing the Slum Clearance and Resettlement Act, Guwahati Municipal

Corporation conducted a second survey in 2008–09. (During the same time they also adopted the new

definition of slums under Circular No.GCS JS/38/07-08/144, dated 02.05.2008 as mentioned under Para 8.11 of the said notification.), ‘a pocket with 25-30 households and lacking basic amenities was considered as slum’. The survey identified 93 slum pockets in 41 wards against the total of 60 municipal wards at the time. The total population recorded was 1.377 lakhs in 28,006 households; which highlights 5 persons per household and constituting 15.33 percent of the total population of Guwahati City at the time.

• Guwahati Development Department, Assam (vide their Notification No. GDD.55/2006/185

dated 27th February 2009) notified four categories of slum pockets in Guwahati City to implement

reforms agenda at the state level and urban local body level under Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) for the all round development of the urban poor in the Guwahati City.

The categories are detailed in table 8.

Based on these categories, a field level investigation and survey was conducted in the entire Guwahati

City from 2011 to the first part of 2013. This survey identified 90 slums, 27,966 households and 167,796 people living in slums. The data collated is represented in table 8.

• Guwahati Municipal Corporation and Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority under the

Guwahati Slum Policy – 2009, identified 90 slum pockets with a population of 167,769 (GMDA, 2009). Refer Map 6

• In addition to GMC/GMDA 2009 survey, an individual researcher Mr. Jatindra Nath Deka in his

2014 publication, ‘Informal Sector among slum inhabitants of Guwahati City’ highlighted an

increase of 24 slum pockets from 2009–2012. The stated report concluded that total slums identified till 2012 was 114 in number with a population of 185,716 and 31,166 households.

• In 2012 several NGOs like Scorpions, RUWA, ACRD, SAMS, Eight Brothers, SRDC, Usgravika conducted a survey in which they identified 217 slum pockets with a population recorded of 1.39 lakh (GMC, 2012). Refer Map 7.

• In 2017 under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, Kamrup Metro another survey was conducted which

concluded 163 slum pockets existing in Guwahati.

The drastic change in the number of slums is due to the change in the definition of slums. In 2009, a pocket with 25–30 households and lacking basic amenities was considered a slum, while for the survey of 2012 a pocket with 10–15 households and without basic amenities was considered a slum. However, according to the collated data, while the number of slums has increased, the slum population has decreased.

Mapping Undertaken

Based on the datasets referenced for the study, the datasets from 2006, 2009 and 2012 are consistent

and conclusive. This is why for a comprehensive understanding of informal settlements in Guwahati City, the timelines 2006, 2009 and 2012 have been used as a base for deliberating the variations in the settlement numbers, households and population of slum dwellers within Guwahati City. A physical mapping exercise of slum settlements identified in the year 2006, 2009 and 2012 onto the GMDA Master Plan 2025 has also been undertaken which adopts the Census definition which identifies 26 slums as per the general definition. (Refer Map 4). The mapping has been done on land-use maps, ecological sensitive zones and reserved land maps. This exercise helps in broadening the perspective to

understand the growth pattern, linkage, informal sector corridors and the interrelationship of land, revenue and politics within the city.

4.2 slum matrix

Existing data on slum settlements from studies was collated, spanning 1986–2012. For purposes of the

study, a consolidated matrix was prepared consisting of information collected and recorded throughout the years of research (Refer to Annexure 4 for more).

The organisations and researchers have collected data on slum settlements for various individual and time-bound studies. The categories of recorded information largely include the names of the settlements, ward numbers, total recorded population during the time of survey and total recorded households. During the time of survey, residents in terms of dominance, nature of land on which the settlement is located, ownership of land on which the settlement is located, land-use and zone was also

detailed. It is important to note that the categories might not be similar in each study and differ based on the intent of each conducted survey.

The exercise of collating the recorded data in one consolidated matrix has helped to understand certain

aspects of slum settlement in Guwahati City which have been divided into the following two categories:

Category 1: Discrepancies in surveys and mapping exercises

The names recorded in surveys of slum settlements tend to vary. This difference in names is due to variation in spelt letters, pronunciation and in some cases the location of the slum. To state an example, Katahbari Garsuk Garopara / Katabari Boro Basti / Katabari Khasiya Ram Boro Path is the same slum that is stated by three different names in three different surveys. Many such similar examples can be found in the matrix.

• In certain surveys, a larger area is recorded under a slum name whereas in another survey smaller pockets of settlements are recorded. To state an example, Dhirenpara Basti is recorded under smaller pockets as Dhirenpara 1, 2, 3, etc. and also recorded based on location as Dhirenpara Milan Path Basti.

• Based on analysis of the collated data, it was observed that some of the slum boundaries were not demarcated in any of the earlier conducted surveys. Cadastral mapping of slum boundaries and geo-referencing the actual locations of the settlements therefore emerged important.

• For some of the settlements the population and household data were recorded but ward numbers were missing, making it difficult to identify the exact location.

• The land-use or land-type on which the settlements are located is of prime importance in the case of Guwahati, because of the peculiarity of its topography and ecologically protected areas. From the earlier surveys some settlements’ land-types categorised under plains, swampy land and hills can be

identified.

Category 2: Evidence based analysis

After collating all the data sets as shown in Table 9 for the slum matrix it was observed that the PMAY

survey conducted in 2017 not only records 163 slums in Guwahati but also their ward numbers and specific ownership of land. Graph 3 illustrates the maximum number of slums located ward-wise along with its ownership details. The data highlights that 24 per cent of the slums are located on railway land, 22 per cent on state government revenue land, 4 per cent on Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) land, 1 per cent on others and 13 per cent on unknown ownership of land.

Based on the matrix and overlay of slum settlements onto the ward boundary map of Guwahati City, it was observed that Ward 3, 7, 12, 13, 14, 53 and 60 have more than five slum settlements in each ward. The reason for concentration in slum numbers in these wards is primarily due to the location, as detailed below:

• Location based on ward and zone: As per the GMC ward boundary, Ward 3, 7,12 and 14 are located in West Zone, Ward 13 is located in outer Lokhra Zone and Ward 53 and 60 is located in Dispur Zone. Wards 3, 7, 12, 13, 14, 53 and 60 lie in the development corridor of the city, resulting in an increased

population density in these wards since 2001. Slums located in Wards 3, 7 and 14 are closer to the central zone of the city with a proximity to commercial areas. Wards 12 and 13 spread from the central zone to the outer zone of the city. Slums located here have access to both the commercial corridor, residential and industrial belt of the city. Wards 53 and 60 situated in Dispur Zone, are an entry point to the city from the south close to the Assam–Meghalaya border and near the industrial corridor. Hence, slums in these wards have increased due to economic and livelihood opportunities.

• Location based on ownership of land: Within Ward 3, 7, 12, 13, 14, 53 and 60, most of the slum settlements are on railway land, spanning across edges of existing and earlier rail-line corridors and railway quarters’ land. Other land ownership types in these wards include state-owned revenue land, Guwahati Municipal Corporation land and also on private miyadi patta land (refer to Table 9 below).

These land types/areas provide the residents of slums with access to economic opportunities in the centre of the city, proximity to schools, amenities and convenience of transportation. Although the residents face multiple threats of eviction and seasonal flooding, the location of the slum provides them

direct access to the resources and opportunities of a city, resulting in the concentration of slums in a few particular wards in the city.

4.3 settlement analysis

For the purpose of this study, seven settlements were selected to understand the nature of planning in

settlements vis-à-vis formal planning practices. The sampling process for selecting seven settlements (Table 10) was purposive, primarily informed by the analysis from the slum matrix and also based on the following criteria:

1. Settlements where YUVA has been engaged

2. Zone-wise distribution - outer, intermediate and inner zones of the city

3. Ward-wise distribution - administrative and local bodies Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC),

Guwahati Development Department (GDD), Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) and other area sabhas

4. Recorded/identified settlements in the surveys conducted in 2006, 2009 and 2012

5. Listed settlements in Rajiv Awas Yojana and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana Demand Survey

6. Listed for rental housing scheme (based on CUE Report)

7. Based on the nature of topography - plains, riverbanks, hills, swampy land, etc.

8. Ownership of land – public, private

9. Land-use (Based on the Master Plan)

10. Located in an ecologically protected zone

Settlements on Railway Land and Hills

• Settlements on Railway Land: Based on GMC’s 2012 slum survey, 8.3 per cent of slums/informal

settlements are located on railway land. In Guwahati, slums on railway land comprise of three types:

1. Slums on vacant land adjacent to the railway tracks are located on narrow strips of vacant land

adjacent to the railway tracks with no access to basic services for the hutments. Evictions take place every year along these railway tracks and the shelters are almost entirely wiped out. E.g. - Lakhtokia gate number 1 to gate number 5, Bhutnath, Santipur

2. Slums on railway land are located on vacant lands in the railway colonies. These areas are also subjected to periodic eviction. E.g. - Bamunimaidan and Gotanagar

3. Slums on large parcels of railway land that are not located near any railway track. Evictions have not taken place in these slums for many years, although there is fear amongst residents that evictions might take place some day because of the land ownership. E.g. - Shakuntala Colony, Kailashnagar in the Pandu area In the Assam Land Policy Act 1989, and Land Policy Amendment Act 2019, there is a provision for those who have done dakhal (illegal occupancy) on state government land to apply for miyadi patta (land ownership) after 15 years of occupying the land. However, no such policy provision exists for railway lands. As a result, one of the important issues in the context of informal settlements and slums in Guwahati is that of insecurity of many of the railway settlements.

• Settlements on Hills:

As Guwahati is a city surrounded by hills, the context of informal settlements on hills and forest lands is inevitable. The threat of eviction is particularly high for those living on reserve forest lands, whose inhabitants include many tribal communities and poor and marginalised migrants.

Among the 90 slums identified under the Guwahati City Slum Policy (Gauhati Municipal Corporation, 2009), over 20 slums (with 5,380 households) are identified as ‘scattered hillside housing’. In 2012, out of 217 slums around 47 slums (21.7 per cent) were identified in the hilly region. Since 2009–2012 there has been a definite increase of hill settlements along the fringe of the city and some settlements like Amsang Basti have faced eviction in the recent past. The state has attempted to label the hill settlements as ‘hill encroachments’ and have plans to evict stating ecological reasons. One such recent forced eviction by the state was in Yusuf Nagar, Nabajyoti Nagar and Kangkan Nagar, Amsang, where

most of the households were destroyed and inhabitants were left stranded, without any clarity on whose land the residents have been settled for years.

In some locations the hills are not occupied by the urban poor and lower-income groups, but have still been recorded and identified as slums. This discrepancy is an added concern.

Similar discrepancies emerge and will continue to face irreversible outcomes due to non-inclusion of slum pockets in the Master Plan and land use plan of the city. The accuracy of governance, slum policy execution and slum upgradation plans stand questionable unless the GMC and GMDA conduct a detailed study on the informal settlements in Guwahati and map the same onto the development plans of the city.

4.4 understanding land use violations

The Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) Master Plan 2025 for Guwahati envisions the creation of affordable housing for all and developing a city without slums. To achieve this vision, one of the main criteria is identifying and mapping the slums to the Master Plan. The GMDA Master Plan report includes a map showing the locations of slums to be upgraded / rehabilitated (Map 4). For the purposes of this study, we analysed the Master Plan 2025 report to get a better understanding of the slum scenario stated by the authorities. In the report GMDA highlights, ‘According to the information provided by the Town and Country Planning Department, Assam, there are 26 slum pockets in the Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) area housing around 0.16 million persons (about 20 per cent of the total population).

The Master Plan 2025 identifies 26 larger areas / pockets where the slums are located and not the individual locations of slums in the city.

Land use zoning is a key factor in a Master Plan that guides urban growth and development. For example, land marked as residential is a broad category under which permitted activities like housing development, combination of housing and commercial development, etc can be proposed. However, when the dataset was geo-referenced and overlaid onto the proposed Master Plan, it was observed that there were several smaller and denser pockets of informal settlements which were spread across the city of Guwahati. The pockets fall under different land use categories as per the proposed Master Plan 2025

(Refer Map 8)

Map 10 shows the Master Plan land use 2025 with an overlay of 217 slums. This overlay analysis highlights slum locations in relevance to land use reservations - 0.9 per cent of slums are located directly on local governing body land, 13 per cent on reserve forest land, 8 per cent on state government land. Table 11 highlights the different percentages of slum locations on land-use master plan. The overlay analysis of the 217 slums shows that almost 37.3 per cent and 21.7 per cent of slums fall on plains and hills. 16.1 per cent of slums falls on private property2. Map 8, 9 and 10 overlay slums (as per 3 data sources) on to the land use map 2025. Maps in Annexure 1.1 - 1.5 overlays slum locations (based on the 2012 NGO survey) over various aspects of the city's land use highlighting the existence of slums across the city, on various reservations and land ownership:

- Guwahati city map showing the hills, green belt and reserve forest land with an overlay of location of slums on plain and hill land type (Annexure 1.1)

- Guwahati Master Plan land use map 2025 overlayed with slums on urban local bodies land (Annexure 1.2) on private property land (Annexure 1.3) on hills, greenbelt and reserve forest land (Annexure 1.4) on state government land (Annexure 1.5)

To better understand the development and growth pattern of seven selected settlements, a method of overlay analysis was devised. To begin with, an approximate physical boundary of the seven settlements was marked onto the Google Image. The boundary is based on the existing extent of the settlements as stated by the residents of the slum. In addition to the overlay study, focus group discussions were conducted in each of the selected seven settlements. The discussion was conducted with the community members to understand the history, growth, occupation, livelihood and amenities

available in and around the settlement.

The findings of the discussion gave insight into the evolution of the informal settlements in Guwahati

and how they have grown in terms of household and populations (Refer Table 12). The discussion also

highlighted that these settlements lack basic amenities like access to safe drinking water and sanitation as a consequence of being excluded from all planning exercises in the city. None of the houses have land tenure or patta, whereas they do possess individual holding numbers, khazana3 and have also paid taxes until 2015 in most cases. In terms of livelihoods, the majority of the male population is engaged as daily wage labourers and the female population as domestic workers or small business owners in the vicinity of their homes. The residents of the surveyed informal settlements reported having heard of the Guwahati Master Plan earlier but were not aware of its details. It is important to note here that the boundary of the settlement is not cadastral mapping.

The boundaries assigned in this study are an assumption to capture the growth of the settlement, rather than showing the extent, value and ownership of land. Further three timelines of years (2003, 2010 and 2019) were selected4 onto which the settlement boundaries were overlapped. This exercise assisted in determining the pattern of development, direction in which the settlement has expanded, changes in the typology and overall growth within and surrounding the slum.